DOCTORS & MEDICAL STUDENTS VERSION

The prevalence of burns that are minor in nature is considerable, with significant burns being a rarity encountered by non-specialist medical staff. Their primary responsibility lies in facilitating the swift and secure transfer of patients to specialized burn units, equipped with intensive care resources and access to proficient burn surgery teams that can provide expert care.

It is imperative that staff familiarize themselves with the ATLS (Advanced Trauma Life Support) and EMSB (Early Management of Severe Burns) protocols. Although major burns constitute only a small fraction of cases presenting at the Emergency Department (ED), those exceeding 15% of the body surface area (BSA) in adults and 10% BSA in children necessitate formal resuscitation and referral to a specialized burns unit. Furthermore, any burns involving the face, hands, feet, or genitalia, irrespective of their size, should be promptly referred to a burns unit.

Upon arrival at the scene, immediate first aid measures are crucial. These measures include removing any burnt clothing and lavaging the burn area with cool, sterile saline for a duration of 10 minutes. This action is pivotal in halting the progression of the burn. Notably, chemical burns require continuous irrigation. To prevent shock, it is recommended to cool the burn while ensuring the patient's overall warmth.

Airway and breathing assessment are of paramount importance. Consultation with an intensive care unit (ICU) anesthetist for a comprehensive airway evaluation is advisable. Administering high-flow oxygen (O2) is crucial, particularly in cases of inhalational injuries caused by thermal or chemical factors. An accurate history is essential, especially for injuries sustained within enclosed spaces.

Inhalational injury indicators encompass direct facial or neck trauma, singed nasal hair, carbonaceous sputum, altered voice, dyspnea, and evidence of soot around the nose or mouth. Systemic edema is infrequent during initial ED presentation but can escalate swiftly with fluid resuscitation. Administering high-flow oxygen is vital, with a focus on maintaining 100% oxygen levels until carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) concentrations are known. If elevated COHb levels persist, continued high-flow oxygen administration is warranted until COHb levels drop below 10% for a minimum of 6 hours.

Formal airway assessment by an anesthetist is advised, and early intubation is often required for major burns before transfer. If intubation becomes necessary, an uncuffed endotracheal tube with an internal diameter exceeding 7.5mm is recommended to facilitate bronchoscope passage. It is crucial to insert a nasogastric tube during intubation, as subsequent swelling can impede its insertion.

Events leading to major burns might result in cervical spine and chest injuries like tension pneumothorax or flail chest. The profound inflammatory response triggered by major burns necessitates substantial fluid volume for resuscitation. Utilizing Hartmann's solution according to the Parklands formula is advised. This entails administering 50% of the calculated fluid volume in the initial 8 hours and the remaining 50% over the subsequent 16 hours. This formula is exclusive to burn resuscitation and does not encompass maintenance or additional fluid needs.

In the initial 24 hours, colloids should be avoided due to their permeability. Blood and clotting agents should be administered as required. Optimal intravenous access through unburnt skin is recommended, and arterial monitoring and central venous access are prerequisites for patient transfer. It is imperative to maintain warmth and prevent any drop in body temperature.

Emergency Medicine Perspective

The Parkland formula provides a foundation for minimum fluid administration during burn resuscitation. However, treatment should be tailored to achieve a urine output of at least 0.5 mL per kg and hematocrit (Hct) below 40%. The objective of fluid administration in burn cases is to anticipate and avert shock.

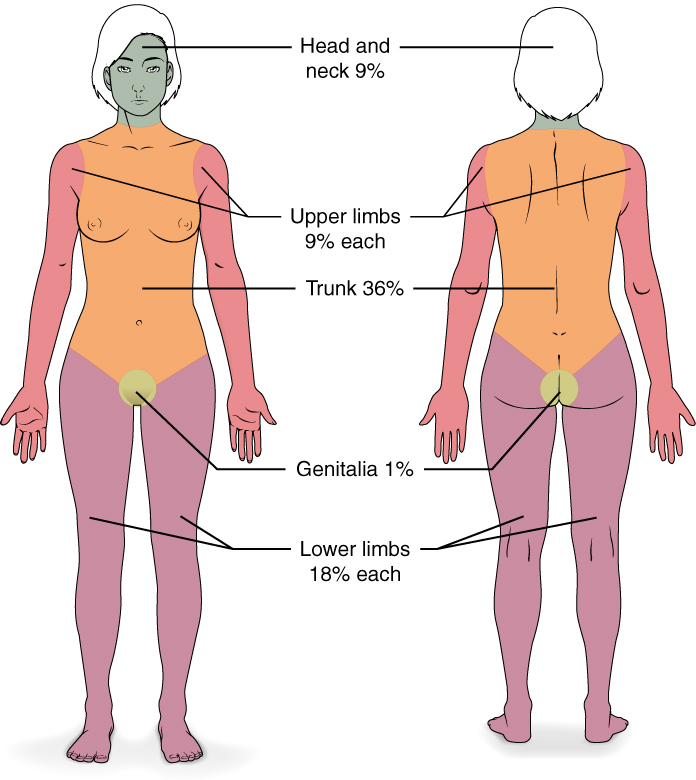

Estimating burn surface area (BSA) can be accomplished using Wallace's Rule of nines or the patient's palm size, where the palmar aspect represents approximately 1% of their BSA. Although the Lund and Browder chart offers greater accuracy, its use is time-intensive.

For assessing burn depth, erythema is a pivotal indicator. Superficial burns display redness, blistering, and intact hair follicles. Deep dermal burns also exhibit redness, pain, and peeling sheets, with fewer intact hair follicles. Full-thickness burns are pale or charred, lack erythema, sensation, and hair, and can cause constriction if circumferential.

In pediatric cases, Wallace's rule of nines requires adaptation, and specialized burn charts are more reliable.

Additional Considerations

Effective pain management is crucial, considering the intense pain associated with burns. Elevating burnt limbs minimizes the risk of compartment syndrome, and continuous monitoring of peripheral pulses is essential. Major burns carry elevated mortality risks, emphasizing the importance of clear communication among medical teams and when discussing treatment options with family members. Predictors of mortality include pre-existing conditions, burn surface area, inhalational injury presence, and patient age.